Inari Ōkami

Inari Okami (Japanese: 稲荷大神), also known as Ō-Inari (大稲荷), is a prominent female deity in Japanese Shinto belief, revered as the goddess of foxes, fertility, rice, tea, sake, agriculture, industry, prosperity, and worldly success. Her name, "Inari," translates literally to "rice-bearer," underscoring her association with agriculture and abundance.

Inari dates back to at least 711 CE with the establishment of a shrine on Inari Mountain, though some scholars trace her origins to the late 5th century. By the 16th century, Inari had become widely revered as the patron of blacksmiths and the protector of warriors.

Inari's popularity soared during the Edo period, spreading across Japan. Today, approximately 40,000 Shinto shrines, including prominent corporate headquarters like Shiseido, dedicate space to Inari worship. Her fox messengers, known as kitsune, are traditionally depicted as pure white and act as intermediaries between Inari and worshippers.

Depiction

[edit | edit source]

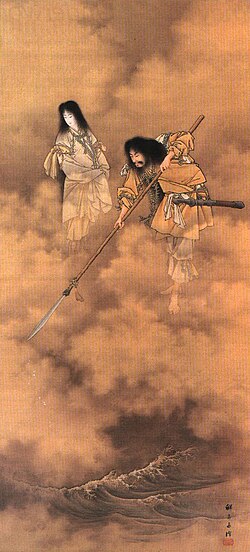

Inari Okami, known as 稲荷大神 (Inari Ōkami) in Japanese, is revered as a principal kami associated with foxes, fertility, rice, tea, sake, agriculture, and industry. Often depicted as a youthful female deity, Inari embodies the attributes of prosperity and abundance in Shinto belief. She is typically represented carrying sheaves of rice or other agricultural produce, symbolizing her role as a provider of sustenance and wealth. Inari's depiction underscores her association with agriculture and the blessings of a bountiful harvest, making her a central figure in the rituals and traditions of Japanese farming communities.

Throughout Japanese history, Inari's representation has evolved while maintaining her primary association with fertility and prosperity. In earlier periods, she was also revered by swordsmiths and merchants seeking success in their respective crafts and trades. Inari's depiction has occasionally been portrayed as both female and male, though she is predominantly recognized as a female kami in modern worship practices. The fluidity in her representation reflects the diverse interpretations and cultural contexts through which Inari has been venerated over centuries.

In contemporary times, Inari continues to be depicted in various forms of art and sculpture, emphasizing her role as a benevolent deity who bestows prosperity and protection upon her devotees. Her imagery remains a prominent feature in Shinto shrines across Japan, where she is honored through rituals and offerings aimed at seeking her blessings for abundant harvests and economic success.

History

[edit | edit source]

Inari's worship dates back to at least 711 CE with the establishment of the first shrine on Inari Mountain, though historical evidence suggests her origins may extend even further back to the late 5th century. Over time, Inari's influence expanded beyond agricultural contexts to encompass protection for warriors and artisans, particularly during the tumultuous periods of Japanese history such as the 16th century. This broadening of her patronage contributed to Inari's widespread popularity and the establishment of numerous shrines dedicated to her worship across Japan.

During the Edo period (1603-1868), Inari's status as a kami of prosperity and protection solidified, leading to the construction of many Inari shrines in urban centers and rural areas alike. Her association with agricultural abundance and economic prosperity made her a revered figure among farmers, merchants, and industrialists seeking her divine favor. Inari's worship flourished within both Shinto and Buddhist traditions, with syncretic practices incorporating elements from both religions to honor her as a benevolent guardian and provider.

In modern Japan, Inari remains one of the most widely venerated kami, with approximately 40,000 shrines dedicated to her across the country. These shrines serve as focal points for community gatherings, festivals, and rituals that celebrate Inari's blessings and seek her guidance in matters of prosperity and well-being. Inari's enduring legacy underscores her significance in Japanese religious and cultural life, where she continues to inspire reverence and devotion among believers seeking her protection and blessings.

Shrines and offerings

[edit | edit source]

Inari is worshipped at thousands of shrines throughout Japan, with Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto being the most renowned. Inari shrines are characterized by vermilion torii gates that mark the transition from the mundane to the sacred. At these shrines, Inari is often depicted in statues and emblems adorned with symbolic representations of rice, sake, and foxes, reflecting her associations with agriculture, fertility, and prosperity. Offerings made to Inari include rice, sake, and Inari-zushi (fried tofu wrapped in seasoned rice), which are presented as tokens of gratitude and petitions for blessings.

The role of kitsune, Inari's white fox messengers, is integral to her worship. Kitsune are revered for their intelligence and spiritual guidance, serving as intermediaries between humans and Inari. They are depicted alongside Inari in various forms of art and sculpture found at her shrines, symbolizing their role in conveying prayers and offerings to the deity. Devotees often make offerings to these kitsune statues, believing that their actions will garner favor from Inari and ensure the fulfillment of their prayers.

Inari's shrines also serve as community centers where festivals and cultural events are held throughout the year. These events celebrate Inari's blessings and include traditional dances, processions, and theatrical performances that highlight her influence on agriculture, commerce, and community prosperity. The vibrant atmosphere at Inari shrines reflects the enduring popularity of her worship and the cultural significance of seeking her divine protection and guidance in daily life.

Personalization

[edit | edit source]

Inari worship is characterized by its personalized approach, allowing devotees to cultivate individual relationships with the deity based on their specific needs and aspirations. Inari is perceived not as a singular entity but as a collective of kami embodying various attributes and manifestations. Devotees may invoke specific aspects of Inari, such as her role as a guardian of prosperity or fertility, depending on their personal circumstances and spiritual goals.

The concept of "personal Inari" (watashi no O-Inari-sama) enables worshippers to connect deeply with the deity, seeking her blessings and protection in matters ranging from agriculture and business to personal relationships and health. This personalized approach is facilitated by Inari's versatile symbolism, which accommodates diverse interpretations and local traditions across Japan. Some devotees may venerate Inari as a protector of family well-being, while others may seek her blessings for success in specific endeavors or ventures.

Kitsune play a crucial role in the personalized worship of Inari, revered as messengers and spiritual guides who convey prayers and offerings to the deity. Devotees often develop close relationships with specific kitsune associated with Inari shrines, viewing them as intermediaries who advocate for their petitions and ensure divine favor. This intimate connection fosters a sense of spiritual closeness and trust between worshippers and Inari, reinforcing her role as a compassionate guardian and benefactor in their lives.

Inari pilgrimage

[edit | edit source]

Pilgrimage to Inari shrines, such as Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto, is a significant spiritual practice among believers seeking blessings and spiritual fulfillment. The pilgrimage experience begins with rituals of purification, symbolizing the cleansing of impurities before entering sacred space. Pilgrims ascend paths lined with thousands of vermilion torii gates, each gate donated as an offering to Inari, marking their journey toward spiritual elevation and divine communion.

The pilgrimage route is not fixed, allowing pilgrims to customize their journey based on personal intentions and spiritual aspirations. Along the way, pilgrims may visit smaller shrines and sacred sites dedicated to Inari and her kitsune messengers, making offerings and receiving blessings from shrine priests. The ascent up Inari Mountain symbolizes a spiritual ascent toward enlightenment and divine favor, with each step reinforcing the pilgrim's dedication and reverence for the deity.

At the summit of the pilgrimage, pilgrims reach the main sanctuary of Fushimi Inari Shrine, where they offer prayers and seek divine guidance from Inari. The descent down the mountain signifies a return to the everyday world, carrying with them the spiritual blessings and protection bestowed by the deity. Pilgrimage to Inari shrines embodies the deep-seated reverence and devotion that believers hold for Inari, blending tradition with personal spirituality in pursuit of harmony, prosperity, and well-being.

Festival

[edit | edit source]

Inari's festival, celebrated across Japan, honors the deity's role as a guardian of prosperity and fertility. The festival typically coincides with the beginning of spring, symbolizing renewal and the planting season. Festivities include rituals of offering rice products, sake, and Inari-zushi at shrines dedicated to Inari, expressing gratitude and devotion for her blessings. These offerings are made to ensure abundant harvests, economic success, and personal well-being in the coming year.

In some regions, Inari's festival spans several days and includes processions, traditional dances, and theatrical performances that celebrate her influence on agriculture and community prosperity. Participants wear traditional attire and carry symbolic offerings as they participate in rituals that seek Inari's favor and protection. The festival atmosphere is vibrant and joyful, reflecting the community's reverence for Inari and her benevolent influence on their lives and livelihoods.

Inari's festival serves as a cultural celebration of Japan's agricultural heritage and spiritual traditions, uniting communities in gratitude and devotion to the goddess of rice and foxes. The annual festivities reaffirm Inari's status as a beloved kami and guardian of prosperity, inspiring worshippers to seek her blessings and guidance for another year of abundance and success.