Fengjian

Fēngjiàn (封建) was a political ideology during the later part of the Zhou dynasty of ancient China, its social structure forming a decentralized system of government[1] based on four occupations, or "four categories of the people." The Zhou kings enfeoffed their fellow warriors and relatives, creating large domains of land. The Fengjian system they created allocated a region or piece of land to an individual, establishing him as the ruler of that region. These eventually rebelled against the Zhou Kings,[2] and developed into their own kingdoms, thus ending the centralized rule of the Zhou dynasty.[3] As a result, Chinese history from the Zhou or Chou dynasty (1046 BC–256 BC) to the Qin dynasty[4] has been termed a feudal period by many Chinese historians, due to the custom of enfeoffment of land similar to that in Medieval Europe. But scholarship has suggested that fengjian otherwise lacks some of the fundamental aspects of feudalism.[5][6] It often related with Confucianism but also Legalism.

Each state was independent and had its own tax and legal systems along with unique currency. The nobles were required to pay regular homage to the king and to provide him with soldiers at the time of war. This structure played an important part in the political structure of Western Zhou which was expanding its territories in the east. In due course this resulted in the rising power of the nobles, who fought among themselves for power, leading to the dwindling authority of the Zhou kings which eventually brought about their downfall.[7]

During the pre-Qin period, fengjian represented the Zhou dynasty political system, and various thinkers, such as Confucius, looked to this system as a concrete ideal of political organization. In particular, according to Confucius, during the Warring States period, the traditional system of rituals and music had become empty and hence his goal was to return to or bring back the Zhou dynasty political system. With the establishment of the Qin dynasty in 220 BCE, the Qin emperor unified the various vassals and abolished fengjian organization, consolidating a new system of rule, namely the junxian (郡縣) or prefectural system. The Qin emperor established thirty-six prefects and created a centralized system to combat dissent by local officials. There are many differences between the two systems, but one is particularly worth mentioning: the prefectural system gave more power to the emperor, since it congealed power at the center or the top. From the Qin dynasty onward, Chinese literati would find a tension between the Confucian ideal of fengjian and the imperial system. [8]

After the establishment of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE to 207 CE), Confucianism became the imperial ideology and scholars and officials again began to look to the Zhou dynasty fengjian system as an ideal. These scholars advocated incorporating elements of the fengjian system into the junxian system. The Han dynasty rulers parceled out land to relatives, thus combining the junxian and fengjian systems. [9]

Four occupations

[edit | edit source]The four occupations were the shì (士) the class of "knightly" scholars, mostly from lower aristocratic orders, the gōng (工) who were the artisans and craftsmen of the kingdom and who, like the farmers, produced essential goods needed by themselves and the rest of society, the nóng (农/農) who were the peasant farmers who cultivated the land which provided the essential food for the people and tributes to the king, and the shāng (商) who were the merchants and traders of the kingdom.

Zongfa (宗法, Clan Law), which applied to all social classes, governed the primogeniture of rank and succession of other siblings. The eldest son of the consort would inherit the title and retained the same rank within the system. Other sons from the consort, concubines, and mistresses would be given titles one rank lower than their father. As time went by, all terms had lost their original meanings nonetheless. Zhuhou (诸侯), Dafu (大夫), and Shi (士) became synonyms of court officials.

The four occupations under the Fēngjiàn system differed from those of European feudalism in that people were not born into the specific classes, such that, for example, a son born to a gong craftsman was able to become a part of the shang merchant class, and so on.

The sizes of troops and domains a male noble would command would be determined by his rank of peerage, which from highest to lowest were:

- duke - gōng 公(爵)

- marquis or marquess - hóu 侯(爵)

- count or earl - bó 伯(爵)

- viscount - zǐ 子(爵)

- baron - nán 男(爵)

While before the Han dynasty a peer with a place name in his title actually governed that place, it had only been nominally true since. Any male member of the nobility or gentry could be called a gongzi (公子 gōng zǐ) (or wangzi (王子 wáng zǐ) if he is a son of a king, i.e. prince).

Well-field system

[edit | edit source]

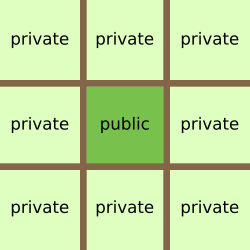

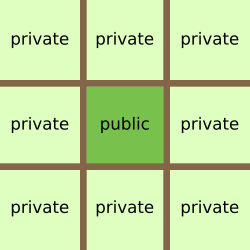

The well-field system (Template:Zh) was a Chinese land distribution method existing between the ninth century BC (late Western Zhou Dynasty) to around the end of the Warring States period. Its name comes from Chinese character 井 (jǐng), which means 'well' and looks like the # symbol; this character represents the theoretical appearance of land division: a square area of land was divided into nine identically-sized sections; the eight outer sections (私田; sītián) were privately cultivated by serfs and the center section (公田; gōngtián) was communally cultivated on behalf of the landowning aristocrat.[10]

While all fields were aristocrat-owned,[citation needed], the private fields were managed exclusively by serfs and the produce was entirely the farmers'. It was only produce from the communal fields, worked on by all eight families, that went to the aristocrats, and which, in turn, could go to the king as tribute.

As part of a larger feudal fēngjiàn system, the well-field system became strained in the Spring and Autumn period[11] as kinship ties between aristocrats became meaningless.[12] When the system became economically untenable in the Warring States period, it was replaced by a system of private land ownership.[11] It was first suspended in the state of Qin by Shang Yang and other states soon followed suit.

As part of the "turning the clock back" reformations by Wang Mang during the short-lived Xin Dynasty, the system was restored temporarily[13] and renamed to the King's Fields (王田; wángtián). The practice was more-or-less ended by the Song Dynasty, but scholars like Zhang Zai and Su Xun were enthusiastic about its restoration and spoke of it in a perhaps oversimplifying admiration, invoking Mencius's frequent praise of the system.[14]

"Feudalism" and Chinese Marxism

[edit | edit source]Marxist historians in China have described Chinese ancient society as largely feudal.[15][16] Fengjian is particularly important to Marxist historiographical interpretation of Chinese history in China, from a slave society to a feudal society.[17] The first to propose the use of this term for the Chinese society was Marxist historian and one of the leading writers of 20th-century China, Guo Moruo[18] in the 1930s. Guo Moruo's views dominated the official interpretation of historical records,[19] according to which the political system during Zhou dynasty can be seen as feudal in many respects and comparable to the Feudalistic system in Europe. Guo Moruo based his application of this term on two assumptions:

The first assumption was based on feudalism being a form of social organization which arises under certain circumstances, mainly the deterioration of a centralized form of government which is replaced by independent feudal states owing only minimal duties and loyalty to a central ruler. This situation is supposed to have prevailed in China after the decline of the Shang dynasty and the conquering of Shang territories by the Zhou clan. One of the reasons for the shift to feudal states is claimed to be the introduction of iron technology.

The second assumption for classifying the Zhou as feudal by Guo Moruo was the similarity of the essential elements of feudalism that included granting of land in form of 'fiefs' to the knighted gentry, as in case of European feudalism. There land fiefs were granted by lords or the ruler to knights, who were considered the ‘vassals’, who in return promised loyalty to the lord and provided military support during periods of war. In China, instead of a salary each noble was given land by the Zhou ruler along with the people living on it who worked on the land and gave part of the produce to the nobles as tax. These 'fiefs' were granted through elaborate ceremonies in Western Zhou, where the plots of land, title and rank were granted in formal symbolic ceremonies which were incredibly lavish and which are comparable to the homage ceremonies in Europe where the vassal took the oath of loyalty and fidelity when being granted land also called ‘fief’. These ceremonies in ancient Zhou period were commemorated in inscriptions on bronze vessels, many of which date back to the early Zhou dynasty. Some bronze vessel inscriptions also confirm involvement of military activity in these feudal relationships.

Comparisons

[edit | edit source]Under the Zhou feudal society, the relationship was based on kinship and the contractual nature was not precise whereas in the European model, the lord and vassal had specific mutual obligations and duties. Medieval European feudalism realized the classic case of the 'noble lord' while, in the middle and latter phases of the Chinese Feudal society, the classic case of the landlord system was to be found.[20] In Europe, the feudal lordships were hereditary and irrevocable and were passed on from generation to generation, whereas the Zhou lordships were not hereditary, required reappointment, and could be revoked. The medieval serf was bound to the land and could not leave or dispose of it, whereas the Zhou peasant was free to leave or, if he had the means, to purchase the land in small parcels. Moreover, in Europe, feudalism was also considered to be a part of an economic system in which the lords who were at the top of the structure, followed by the vassals, and then the peasants who were tied to the land and were responsible for the production.

In Zhou rule, the feudal system was not responsible for the economy. Furthermore, according to China-A New history by John K. Fairbank and Merle Goldman, dissimilarities existed between the merchant class of the two systems as well.[21] In feudal Europe, the merchant class saw a marked development in towns away from the manors and villages. The European towns could grow outside of the feudal system instead of being integrated in them since the landed aristocrats were settled in the manors. Thus, the towns were independent from the influence of the feudal lords and were solely under the authority the Kings of the kingdoms. In China, these conditions were non existent and the King and his officials depended greatly on the landed gentry. Thus no political power was available to encourage the growth of the merchant class in an independent manner. Towns and villages were an integrated system and merchants remained under the control of the gentry class instead of setting up an independent trade and economy.[22]

Regardless of the similarities of the agrarian society being dominated by the feudal lords in both societies, the application of the term 'feudal' to the Western Zhou society has been a subject of considerable debate due to the differences between the two systems. The Zhou feudal system was termed as being 'protobureaucratic' (The Prehistory and Early History of China – by J.A.G. Roberts) and bureaucracy existed alongside feudalism, while in Europe, bureaucracy emerged as a counter system to feudal order. Therefore, according to some historians the term feudalism, is not supposed to be an exact fit to the Western Zhou political structure but it can be considered a system analogous to the one that existed in medieval Europe. According to Terence J. Byres in Feudalism and Non European Societies, "feudalism in China no longer represents a deviation from the norm based on European feudalism, but is a classic case of feudalism in its own right."[23]

See also

[edit | edit source]- Agriculture in China

- Economic history of China

- Ejido

- Equal-field system

- Sharecropper

- Tenancy

- Indian feudalism

- Feudal Japan

- Feudalism in Pakistan

- Ritsuryō

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ V MURTHY. MODERNITY AGAINST MODERNITY: WANG HUI'S CRITICAL HISTORY OF CHINESE THOUGHT. Modern Intellectual History, 2006 – Cambridge Univ Press

- ↑ "thinkquest.org". Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ↑ Levenson, Schurmann, Joseph, Franz (1969). China-An Interpretive History: From the Beginnings to the Fall of Han. London, England: Regents of the University of California. pp. 34–36. ISBN 0-520-01440-5.

- ↑ http://totallyhistory.com/zhou-dynasty-1045-256-bc/

- ↑ www.chinaeducenter.com. "History of Zhou Dynasty - China Education Center". chinaeducenter.com. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. "Chinese History - Zhou Dynasty 周 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ↑ Roberts, John A.G (1999). A Concise History of China. First United Kingdom. pp. 9–12. ISBN 0-674-00074-9.

- ↑ Roberts, John A.G (1999). A Concise History of China. First United Kingdom. pp. 9–12. ISBN 0-674-00074-9.

- ↑ Roberts, John A.G (1999). A Concise History of China. First United Kingdom. pp. 9–12. ISBN 0-674-00074-9.

- ↑ Zhufu (1981:7)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Zhufu (1981:9)

- ↑ Lewis (2006:142)

- ↑ Zhufu (1981:12)

- ↑ Bloom (1999:129–134)

- ↑ Dirlik, Arif (1985). Feudalism and Non European Societies. London: Frank Cass and Co. limited. pp. 198, 199. ISBN 0-7146-3245-7.

- ↑ http://www.hceis.com/chinabasic/history/zhou%20dynasty%20history.htm

- ↑ QE WANG. Between Marxism and Nationalism: Chinese historiography and the Soviet influence, 1949–1963 – Journal of Contemporary China, 2000 – Taylor & Francis

- ↑ The Prehistory and early history of china – by J.A.G. Roberts

- ↑ Byres, Terence; Mukhia, Harbans (1985). Feudalism and non European societies. London: Frank Cass and Co. limited. p. 213. ISBN 0-7146-3245-7.

- ↑ Byres, Terence; Mukhia, Harbans (1985). Feudalism and Non European Societies. London: Frank Cass and Co. pp. 213, 214. ISBN 0-7146-3245-7.

- ↑ Fairbank, John; Goldman, Merle (1992). China-A new history. United states of America: President and Fellows of Harvard College. ISBN 0-674-01828-1.

- ↑ China-A New history'by John K Fairbank and Merle Goldman

- ↑ Byres, Mukhia, Terence, Harbans (1985). Feudalism and Non European Societies. London: Frank Cass and Co. p. 218. ISBN 0-7146-3245-7.

Bibliography

[edit | edit source]- Bloom, I. (1999), "The evolution of Confucian tradition in antiquity", in De Bary, William Theodore; Chan, Wing-tsit; Lufrano, Richard John; et al. (eds.), Sources of Chinese Tradition, 2, New York: Columbia University Press

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2006), The Construction of Space in Early China, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Wu, Ta-k'un (1952), "An Interpretation of Chinese Economic History", Past & Present, 1 (1): 1–12, doi:10.1093/past/1.1.1

- Zhufu, Fu (1981), "The economic history of China: Some special problems", Modern China, 7 (1): 3–30, doi:10.1177/009770048100700101

Works cited

[edit | edit source]- The Prehistory and Early History of China – by J.A.G. Roberts

- China-A New history by John K. Fairbank and Merle Goldman

- Byres, Terence and Harbans Mukhia, (1985). Feudalism and non European societies. Stonebridge Press, Bristol. pp. 213, 218, ISBN 0-7146-3245-7

- Levenson, Schurmann, Joseph, Franz (1969). China-An Interpretive History: From the Beginnings to the Fall of Han. London, England: Regents of the University of California. pp. 34–36. ISBN 0-520-01440-5.

- Dirlik, Arif (1985). Feudalism and Non European Societies. London: Frank Cass and Co. limited. pp. 198, 199. ISBN 0-7146-3245-7

- China Travel Discovery

- http://www.hceis.com/chinabasic/history/zhou%20dynasty%20history.htm

- http://www.hceis.com/chinabasic/history/zhou%20dynasty%20history.htm#Kings

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130531215622/http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Zhou/zhou-admin.html 1st para

- http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Zhou/zhou.html